Wealth management firms have traditionally been required to pursue three potentially competing strategic imperatives. They must strive for long-term, personal relationships with their clients while simultaneously developing innovative products and services, and building efficient and resilient processes and systems. A sharp increase in digital competition across the wealth management and investing arena is exacerbating the inherent conflict between these competing internal priorities, calling traditional management common sense into question.

Picture the executive board of a traditional wealth management firm discussing its current priorities and future strategic plans.

In addition to the Chief Executive Officer, around the table we have a Chief Investment Officer responsible for the firm’s investment products and strategies, a Client Services Director responsible for those all-important client relationships, and a Head of Operations responsible for the firm’s processes and infrastructure, including IT.

The CEO will naturally attempt to balance the competing needs, cultures and incentives represented by these three individuals in order for the firm to excel across all three areas of value creation.

For example, in order to develop innovative capital growth and income strategies, the firm would need to prioritise speed to market with a narrow focus. New ideas need to be tried out, and the more experimental the approach, the more it would need to be ‘allowed to fail’. This rapid feedback loop will help the firm bring out fresh ideas that help to differentiate the firm in the eyes of demanding investors.

However, some voices around the boardroom table might understandably object that this could put the firm’s high-quality personal service ethos at risk. They may argue that a ‘move fast and break things’ strategy hardly works when dealing with real people’s portfolios. On the other hand, what if new portfolio offerings turn out to be wildly popular? Systems designed with different approaches in mind may struggle to deliver the new service at scale in terms of quality and cost-efficiency. Either way, innovation starts to sound risky.

Looking at the firm’s other high-level aims, everyone agrees that its strengths and reputation depend on building deeper, more personal relationships with greater numbers of unique and demanding investors. The broader the range of customer needs that can be satisfied, and the wider the range of different clients that can be served, the better. But when it comes to the practicalities of this ever-widening scope, there are some cautionary voices. The better the firm gets at bespoke, almost concierge-like services for private clients, the worse it may perform in terms of standardising its scalable, efficient infrastructure or achieving the focus needed for true innovation.

Moving on to the goal of standardising and scaling the firm’s infrastructure to improve global reach and cost efficiencies, again, everyone agrees this seems self-evidently important. That is, until the practicalities of operational standardisation and cost-limiting initiatives sound like they will negatively impact levels of personal service. Others agree that creating restrictions or frictions for the people working to invent and trial new products will damage competitiveness.

This is far from straightforward: the board knows that the autonomy required for each department to pursue its strategy successfully may actually result in them contradicting and competing with each other. Yet if it attempts to pursue all three strategies, the firm may struggle to achieve any of them successfully.

The generalist business model

Whether it’s a private bank, family office, stockbroker or investment manager, the scenario above is a classic example of a generalist operating model in which a firm attempts to do a little bit of everything well and, as a result, can end up failing to do any one of them exceptionally.

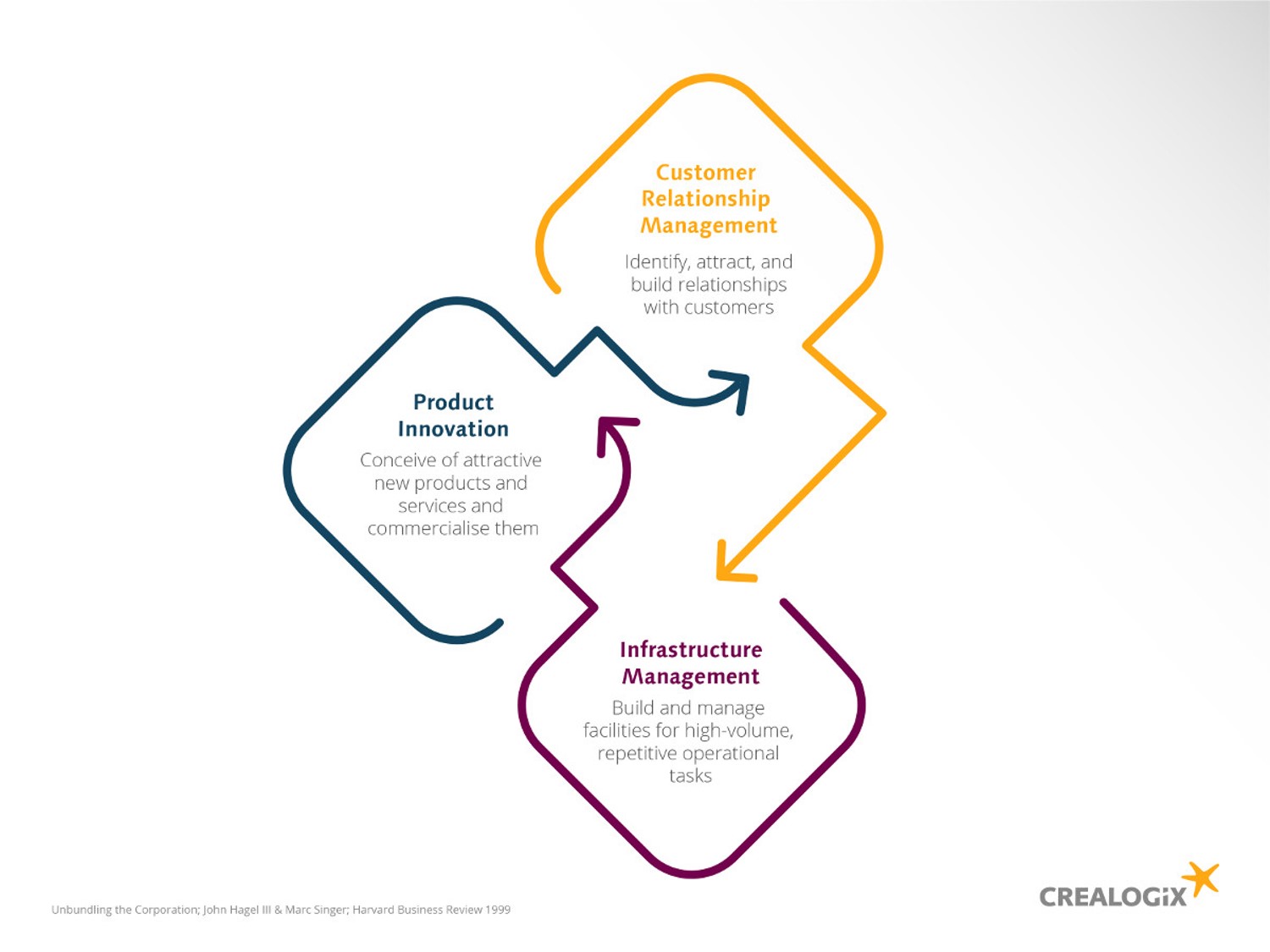

The inherent conflicts in this model were first identified more than 20 years ago by John Hagel III and Marc Singer in a Harvard Business Review article in which the authors suggested that there are always three separate business models operating within every traditional business:

- Product design and innovation

- Customer relationship management

- Infrastructure management

They argued that most traditional businesses tend to be generalists, meaning all three of these value creation engines exist within the business, and the leadership team find themselves trying to ensure the integrity of the business as a whole. To do so, they have to continually balance these three areas, thereby effectively limiting the full potential for growth or specialisation in any particular operational direction. This leads to inefficiencies and reduces the chances of success, compared to more focused alternative strategies. As Hagel and Singer anticipated a few years before the first dot-com rush, the digital era allows for the realisation of such truly focused strategies.

Every business can ask itself these questions: while our different teams may have brilliant ideas about how to build excellent client relationships, how do we develop innovative product strategies, and how do we build systems upon which the organisation can gain scale and efficiency? Are we really able to become exceptional in any of these areas? Or are these aims constantly being thwarted in order for the overall generalist business model to be maintained? What would it mean to become truly focused on just one value creation engine?

Fit for purpose?

In wealth management, the classic general-purpose business model is increasingly being called into question by the need for firms to address digital threats and opportunities, and the change management implied by rapidly ‘upskilling’ to use technology.

New external sources of competitive pressures include:

- new digital wealth management challengers, including robo-investing brands and peer-to-peer lending platforms

- digital-native services offering access to a plethora of alternative investments – from cryptocurrencies to fine art

- the looming threat of big tech entering the savings and investment space.

Taken together, digital competition has heightened the urgency of improving performance in all three value engines: implementing new ideas to match changing investor behaviours, keeping existing clients loyal and attracting new investors, and improving scalability and profitability. But the more the established firms try to improve, the more they will be confronted by the tensions that arise from attempting to pursue a range of conflicting business activities under one roof.

Challengers are less likely to suffer from these internal tensions: their business models tend to focus on a single value creation activity – customer relationship management, or infrastructure and processes, or product innovation – rather than trying to balance all three imperatives. Digitally native businesses usually become expert in a single target area of excellence and use this focus to build market share at the expense of legacy businesses, whose resources and attention are more stretched.

What would it look like for established wealth management firms to stop trying to ‘do everything, adequately well’ and instead challenge themselves to select a single value creation area at which to lead the market?

It has previously been the norm for a firm to create its own investment products and build various heavily customised technology platforms to manage its investment strategies and clients, while sticking firmly to a ‘bespoke’ view of client relationship management. It’s not going to be easy to accept a reduced emphasis on any of these. But if the firm could find a way to commit to just one main strategic focus out of these three, it would immediately become clear where it’s preferable to cut or limit internal efforts elsewhere, and thus be able to find the right third parties for complementary products, services and partnerships.

Partner for success

In any industry, a general-purpose business model is no match for an array of focused specialists: in wealth management it’s becoming increasingly necessary to ask “what business are we really in?” and take the specialist path to differentiation that plays to established strengths.

For financial institutions that were established decades (and in some cases centuries) before the digital era, software and IT are areas where it commonly does not make sense for a firm to attempt to do everything under one roof, when there are so many advanced specialists that will do the work better and faster.

The key for an ‘unbundled’ firm is knowing exactly what they don’t want to do in-house so that the search for the right partners becomes clearer and focused on primary business objectives.

In conclusion, although many of the pressures on established financial brands are digital, and therefore require responses in digital strategy and capability, it doesn’t follow that established wealth management firms need to transform themselves into technology businesses in order to compete. By questioning what the firm is truly good at, and committing to a clear vision, it becomes possible to concentrate more fully on a few core sources of differentiation.

At the same time, this strategic exercise reveals which of the current operating components and commitments would be better ‘unbundled’ and taken care of by external specialists, who can pursue excellence without it causing contention or scope creep for the core in-house value creators.

The strategic shift from “we can do it all adequately well” to “we do these few things far better than anyone else, and work with partners to deliver everything else” will be transformative for any organisation. It is this strategic transformation, rather than a narrow or reactive digital transformation, which will allow wealth management firms to harness their years of experience and depth of expertise. From this footing, wealth management firms can choose and exploit the technology that aligns with their strengths, and compete effectively in the digital era.

Read more about “unbundling the corporation” for wealth management in our follow-up piece in The Wealth Mosaic: Do wealth management firms need to become technology businesses?